Install the app

How to install the app on iOS

Follow along with the video below to see how to install our site as a web app on your home screen.

Nota: This feature may not be available in some browsers.

Je gebruikt een verouderde webbrowser. Het kan mogelijk deze of andere websites niet correct weergeven.

Het is raadzaam om je webbrowser te upgraden of een alternatieve webbrowser te gebruiken.

Het is raadzaam om je webbrowser te upgraden of een alternatieve webbrowser te gebruiken.

FORUMLEDEN met NOSTALGIE......"vreemde" kisten

- Topicstarter steffe

- Startdatum

- Status

- Niet open voor verdere reacties.

Wel een leuk project.. (nog steeds in ontwikkeling)

Meer informatie:

http://www.strongware.com/dragon/

[video width=400 height=350:0838c0e2f6]http://www.strongware.com/dragon/dragon.wmv[/video:0838c0e2f6]

Dus maar een nieuwe:

Max Horlacher has completed a range of experimental projects proving the exceptional possibilities of lightweight, composite materials-based construction methods.

Materials such as e.g. carbon fibre, Kevlar®, Mylar® foils, Nomex® honey-combs and epoxy resins have been used in the following HPV (Human Powered Vehicle) projects:

Human powered aircraft:

Pelargos (1983)

Wing span: 26 m

Weight: 36 kg

Flight distance: 800 m (airport runway)

> ALHIER < de link

Wim

[toevoeg]

Even ge plaatjes-googled op Pelargos.

Ik krijg dan alleen de opvolger van bovenstaande, nl:

Pelargos 2:

Pelargos 2 is a huge and slow HPA, one can easily run with it. We flew it in Dübendorf CH.

span 27m

wing area 67.5 m2

aspect ratio 10.8

wing type high wing, rectangular planform, multi wire, sandwich tube spar, molded ribs

controls rudder and elevator only

minimum power flight speed 19 km/h (10 KEAS)

1st flight December 1983 in Dübendorf CH

design & fabrication Max Horlacher & Toni Felix

layout Prof. Fritz Dubs, Zürich

Daarna kwam er ook nog de

Pelargos 3:

Pelargos 3 is much smaller and refined than Pelargos 2. We flew it in Birrfeld CH.

Span 22m

wing area 19.8 m2

aspect ratio 24.4

wing type high rectangular, strut, single wire, sandwich tube spar, molded ribs

controls rudder and elevator only

empty weight 42kg

minimum power flight speed 28 km/h (15 KEAS)

1st flight April 1985 in Birrfeld CH

design & fabrication Max Horlacher & Toni Felix

layout P. Frank

Aan bovenstaande gegevens te zien is de opgave dus de Pelargos (1)

[/toevoeg]

Materials such as e.g. carbon fibre, Kevlar®, Mylar® foils, Nomex® honey-combs and epoxy resins have been used in the following HPV (Human Powered Vehicle) projects:

Human powered aircraft:

Pelargos (1983)

Wing span: 26 m

Weight: 36 kg

Flight distance: 800 m (airport runway)

> ALHIER < de link

Wim

[toevoeg]

Even ge plaatjes-googled op Pelargos.

Ik krijg dan alleen de opvolger van bovenstaande, nl:

Pelargos 2:

Pelargos 2 is a huge and slow HPA, one can easily run with it. We flew it in Dübendorf CH.

span 27m

wing area 67.5 m2

aspect ratio 10.8

wing type high wing, rectangular planform, multi wire, sandwich tube spar, molded ribs

controls rudder and elevator only

minimum power flight speed 19 km/h (10 KEAS)

1st flight December 1983 in Dübendorf CH

design & fabrication Max Horlacher & Toni Felix

layout Prof. Fritz Dubs, Zürich

Daarna kwam er ook nog de

Pelargos 3:

Pelargos 3 is much smaller and refined than Pelargos 2. We flew it in Birrfeld CH.

Span 22m

wing area 19.8 m2

aspect ratio 24.4

wing type high rectangular, strut, single wire, sandwich tube spar, molded ribs

controls rudder and elevator only

empty weight 42kg

minimum power flight speed 28 km/h (15 KEAS)

1st flight April 1985 in Birrfeld CH

design & fabrication Max Horlacher & Toni Felix

layout P. Frank

Aan bovenstaande gegevens te zien is de opgave dus de Pelargos (1)

[/toevoeg]

Nog even terug komen op de Pucara, want dat was mijn opgave inderdaad. Dit is GEEN foto van een RC model! Deze foto is gemaakt in Argentinië net na het opstijgen en het intrekken van het landingsgestel. De foto is gemaakt door een vriend van mij in Engeland. Hij was jaren terug in Argentinië en heeft daar deze foto, en nog vele andere gemaakt. Hij is toen wel door het oog van de naald gekropen want wat hij deed kon toen als spionage gezien worden. Als hij gesnapt zou zijn had hij, voor lange tijd, in het gevang terecht kunnen komen. :roll:

Tja, dat risico zit er nu natuurlijk wel in. Een topic van dik 100 bladzijden.

Ik heb ze (als botenman) niet allemaal bekeken.

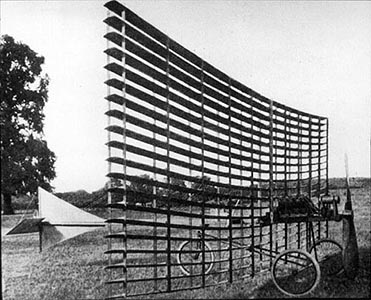

OK, deze dan:

Ik weet geen naam van dit vlieg-"ding". Weet wel dat het 500 voet heeft gevlogen (ik neem niet aan dat dit de hoogte is )

)

Daarom: de naam van de ontwerper en het jaar van ontstaan van dit "ding"

Wim

[edit]

Het "ding" heeft WEL een naam. Welke?

[/edit]

Ik heb ze (als botenman) niet allemaal bekeken.

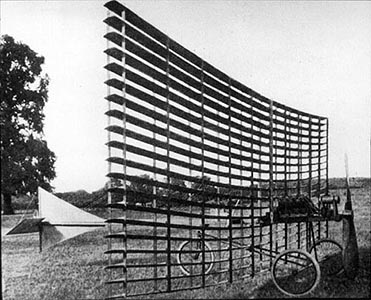

OK, deze dan:

Ik weet geen naam van dit vlieg-"ding". Weet wel dat het 500 voet heeft gevlogen (ik neem niet aan dat dit de hoogte is

Daarom: de naam van de ontwerper en het jaar van ontstaan van dit "ding"

Wim

[edit]

Het "ding" heeft WEL een naam. Welke?

[/edit]

P

Pjotrrr

Guest

Goh, had je toen ook al designradiators voor de badkamer?

P

Pjotrrr

Guest

1907: Horatio Philips 'Flying Venetian Blind'

Eerste vliegtuig dat een 'hop' van 500 ft haalt in Engeland...

Meer van zijn ontwerpen:

http://firstflight.open.ac.uk/phillips/phillips_aircraft01.html

Zoals deze uit 1904:

Eerste vliegtuig dat een 'hop' van 500 ft haalt in Engeland...

Meer van zijn ontwerpen:

http://firstflight.open.ac.uk/phillips/phillips_aircraft01.html

Zoals deze uit 1904:

P

Pjotrrr

Guest

Volgende kist vloog in 1949 en had een grotere spanwijdte als een 747!!!

P

Pjotrrr

Guest

Hi Wim,

Een specifieke naam voor die kist stond er op genoemd linkje niet bij.....

Maar we mogen verder hoop ik?

Peter

Een specifieke naam voor die kist stond er op genoemd linkje niet bij.....

Maar we mogen verder hoop ik?

Peter

Dirk zei:Een echte Bristol Brabazon ....

Klopt, die weet ik uit mijn hoofd..

Damm ben ik ook een paar minuutjes weg....

P

Pjotrrr

Guest

Mooi he...

When the Brabazon Committee's intercontinental airliner was proposed, however, the work already done by Bristol late in WW2 on their heavy bomber design led to them being given an order for two prototypes, to be followed by a possible ten production aircraft.

After considering a variety of capacity and design criteria, in November 1944 the concept solidified around a 177 ft. fuselage with 230 ft wingspan (35 ft. more than a Boeing 747), powered by eight Bristol Centaurus 18-cylinder radial engines nested in pairs in the wing. These drove eight paired counter-rotating propellors on four forward-facing nacelles.

The Brabazon project team were among the best and brightest of their time, and they developed what was probably the first instance of an aircraft designed with an optimal structure. Structural components, including the skin, were designed to meet load requirements whilst having only minimal weight. Skin panels were machined to closer tolerances than ever, and to non-standard gauges. Weight savings through innovation and sophistication could be measured in tons.

The large span and mounting of the engines close inboard, together with structural weight economies, demanded some new measure to prevent bending of wing surfaces in turbulence. A system of gust alleviation was developed for the Brabazon, using servos triggered from a probe in the aircraft's nose. Hydraulic power units were also designed to operate the giant control surfaces.

The Brabazon was the first aircraft with 100% powered flying controls, the first with electric engine controls, the first with high-pressure hydraulics, and the first with AC electrics.

Construction commenced on the Brabazon in October 1945, in a specially-built 8-acre assembly building adjoining a new, strengthened 8,000 ft. runway. This last structure was built in the face of an out-of-date Civil Airworthiness Requirement, which insisted upon the use of runways no longer than 2,000 feet, forcing a landing speed of around 60 mph. This in turn demanded a low wing loading, and thus an increased wing area. Long, narrow wings are more efficient, having lower drag, but long, strong wings were demanding on the techniques of the time, and tended to be heavy.

The solution for Brabazon was to bury the engines in the wings, near the props. This in itself reduced drag on the engines. It made the wings substantially thicker, but it also enabled the wings to be made lighter and stronger.

The aircraft rolled out for engine runs in December 1948. On 4th September, 1949, chief test pilot "Bill" Pegg took the Brabazon up for her first flight. Most of the work force and thousands of other spectators cheered as the aircraft climbed majestically, flew around, and landed.

The aircraft was free of any major problems, especially considering the many groundbreaking technological applications in the design. Everyone who flew in it was impressed by its quietness and smoothness and its spacious interior.

Back in 1946, it had already been decided that a Brabazon Mk.II would be built with four Bristol Coupled Proteus turboprops, driving an eight-bladed contra-prop. These would save an estimated five tons in weight and boost the top speed to 330 mph at 35,000 ft. It would also impose greater airframe stresses which would have to be addressed.Four days after her first flight, the Brabazon prototype, G-APGW, appeared at the Farnborough Air Show. During June 1950 she visited London's Heathrow Airport, making a number of successful takeoffs and landings, and was demonstrated at the 1951 Paris Air Show. By now about £3.4m had been spent on development. However, half of that went into infrastructures, including massive hangars and the long runway, both of which remained in use for decades.

The Brabazon was to fail for reasons of economics. She was conceived following an era when passenger flying in England and Europe was the domain of civil servants in transit, business executives and the well-off. The airliner was viewed in the same light as the ocean liner. BOAC considered passengers would find a long non-stop flight almost intolerable and should therefore be provided with 200 cu. feet for comfort, and 270 cu. ft. for luxury. This equates with about three times the interior size of a modern family car, per airline passenger.

The 1944 version of the proposed airliner gave it a 25 ft. diameter fuselage (about 5 ft. greater than a Boeing 747) with upper and lower decks. This enclosed sleeping berths for 80 passengers, a dining room, promenade and bar; or day seats for 150 people. The Committee recommended a narrower fuselage designed for 50 passengers. BOAC agreed, but preferred a design for only 25 passengers.

Etcccc....: http://www.unrealaircraft.com/classics/brab.php

NEXT!!!

When the Brabazon Committee's intercontinental airliner was proposed, however, the work already done by Bristol late in WW2 on their heavy bomber design led to them being given an order for two prototypes, to be followed by a possible ten production aircraft.

After considering a variety of capacity and design criteria, in November 1944 the concept solidified around a 177 ft. fuselage with 230 ft wingspan (35 ft. more than a Boeing 747), powered by eight Bristol Centaurus 18-cylinder radial engines nested in pairs in the wing. These drove eight paired counter-rotating propellors on four forward-facing nacelles.

The Brabazon project team were among the best and brightest of their time, and they developed what was probably the first instance of an aircraft designed with an optimal structure. Structural components, including the skin, were designed to meet load requirements whilst having only minimal weight. Skin panels were machined to closer tolerances than ever, and to non-standard gauges. Weight savings through innovation and sophistication could be measured in tons.

The large span and mounting of the engines close inboard, together with structural weight economies, demanded some new measure to prevent bending of wing surfaces in turbulence. A system of gust alleviation was developed for the Brabazon, using servos triggered from a probe in the aircraft's nose. Hydraulic power units were also designed to operate the giant control surfaces.

The Brabazon was the first aircraft with 100% powered flying controls, the first with electric engine controls, the first with high-pressure hydraulics, and the first with AC electrics.

Construction commenced on the Brabazon in October 1945, in a specially-built 8-acre assembly building adjoining a new, strengthened 8,000 ft. runway. This last structure was built in the face of an out-of-date Civil Airworthiness Requirement, which insisted upon the use of runways no longer than 2,000 feet, forcing a landing speed of around 60 mph. This in turn demanded a low wing loading, and thus an increased wing area. Long, narrow wings are more efficient, having lower drag, but long, strong wings were demanding on the techniques of the time, and tended to be heavy.

The solution for Brabazon was to bury the engines in the wings, near the props. This in itself reduced drag on the engines. It made the wings substantially thicker, but it also enabled the wings to be made lighter and stronger.

The aircraft rolled out for engine runs in December 1948. On 4th September, 1949, chief test pilot "Bill" Pegg took the Brabazon up for her first flight. Most of the work force and thousands of other spectators cheered as the aircraft climbed majestically, flew around, and landed.

The aircraft was free of any major problems, especially considering the many groundbreaking technological applications in the design. Everyone who flew in it was impressed by its quietness and smoothness and its spacious interior.

Back in 1946, it had already been decided that a Brabazon Mk.II would be built with four Bristol Coupled Proteus turboprops, driving an eight-bladed contra-prop. These would save an estimated five tons in weight and boost the top speed to 330 mph at 35,000 ft. It would also impose greater airframe stresses which would have to be addressed.Four days after her first flight, the Brabazon prototype, G-APGW, appeared at the Farnborough Air Show. During June 1950 she visited London's Heathrow Airport, making a number of successful takeoffs and landings, and was demonstrated at the 1951 Paris Air Show. By now about £3.4m had been spent on development. However, half of that went into infrastructures, including massive hangars and the long runway, both of which remained in use for decades.

The Brabazon was to fail for reasons of economics. She was conceived following an era when passenger flying in England and Europe was the domain of civil servants in transit, business executives and the well-off. The airliner was viewed in the same light as the ocean liner. BOAC considered passengers would find a long non-stop flight almost intolerable and should therefore be provided with 200 cu. feet for comfort, and 270 cu. ft. for luxury. This equates with about three times the interior size of a modern family car, per airline passenger.

The 1944 version of the proposed airliner gave it a 25 ft. diameter fuselage (about 5 ft. greater than a Boeing 747) with upper and lower decks. This enclosed sleeping berths for 80 passengers, a dining room, promenade and bar; or day seats for 150 people. The Committee recommended a narrower fuselage designed for 50 passengers. BOAC agreed, but preferred a design for only 25 passengers.

Etcccc....: http://www.unrealaircraft.com/classics/brab.php

NEXT!!!

- Status

- Niet open voor verdere reacties.